“A game is only late until it ships, but it’s bad forever.”

Siobhan Beeman, quoted by Ellen Guon at the 1996 Computer Game’s Developers Conference (found by Kate Willaert)

Today, video games and other media form the backbone of what we call “hype culture”. Products are anticipated, showcased in their early states, and placed into release slots long in advance of their finalization. This extends from movies to phones to graphics cards. Consumers are pushed into investing into something which will be on the market at some distant point in the future rather than immediately. For those who have grown up into this culture, it can be difficult to understand that even the biggest advertising pushes did not promote product on some distant horizon. Such a thing would have been practically inconceivable to a consumer of the 1970s or 1980s in video games.

When I use the term “hype culture” in this context, it does not mean there was never any highly anticipated titles in the video gaming’s past nor that there were not games announced well before release. What there was not though was a concerted marketing effort banking on the enthusiasm of consumers to follow these releases. Prior to the instant proliferation of knowledge via the internet in the mid to late 90s, game development was an abstract concept. Only those with a tech interest would be following the scant bits of knowledge about game development and game developers in the magazines and newspaper profiles. Trusting in the potential of a specific developer was not something that a large portion of game players did.

Having that understanding, we can begin to examine what it was like to anticipate games as well as why game development became a promotional tool.

At the beginning of commercial video games, the category was slotting into existing industries. For the arcade that was coin-op and for the home that was retail, specifically department store retail. Neither of these markets were particularly concerned with when product was coming out as long as it arrived regularly to fill the shelves. Part of the reason for this was that logistics in shipping – for both sectors – could not guarantee that an item would arrive simultaneously at stores across the country. This may not seem like a great deal in the grand scheme of things, but back in the day stores were competing to have the first product to draw in customers.

Department stores especially as the first line of video game retail in the late 70s and early 80s had a great incentive to get families in their stores with the promise of future purchases. They would provide a list by which they could guarantee a piece of incoming inventory to a customer that paid upfront. This wasn’t a pre-order as the allotments were already en route, but it was a promise that becoming part of the department store’s “system” would grant you a first spot in the line. This early form of data collection was incentivized by advertising the availability of a product they couldn’t guarantee would be in stores. The store would say they had a new game, say they were sold out, then get that person on the list.

There wasn’t much to anticipate in the early days. With games being so new, even the semi-familiar Atari arcade ports were only known quantities to a very small portion of their audience. Not much crossover existed between players of coin-op games and players of home games in the beginning, they were distinctly separate markets catering to different types of people. Video games on location were for the older set, physically adjusted to the height of a full grown adult and placed in locations where younger people didn’t normally wander. Younger people involved with the hobby had the opportunity to replicate the same sort of feeling on a home console which was a controlled expense by parents. For the longest time these existed as separate tracts. Until Space Invaders.

With the impact of Space Invaders incentivizing players of all types to become involved in the new arcade game phenomenon, it became a name synonymous with said shift in culture. Therefore, when Atari decided to make a home game version of it, for the first time such a thing was announced ahead of time. Profiles dropped in January of 1980 for the anticipated release in March of that year. However, even though they set a plan for two months ahead, the earliest evidence of the game being available was at the end of February that year. This again highlights the inconsistencies of shipping and how no game was truly set for a release date.

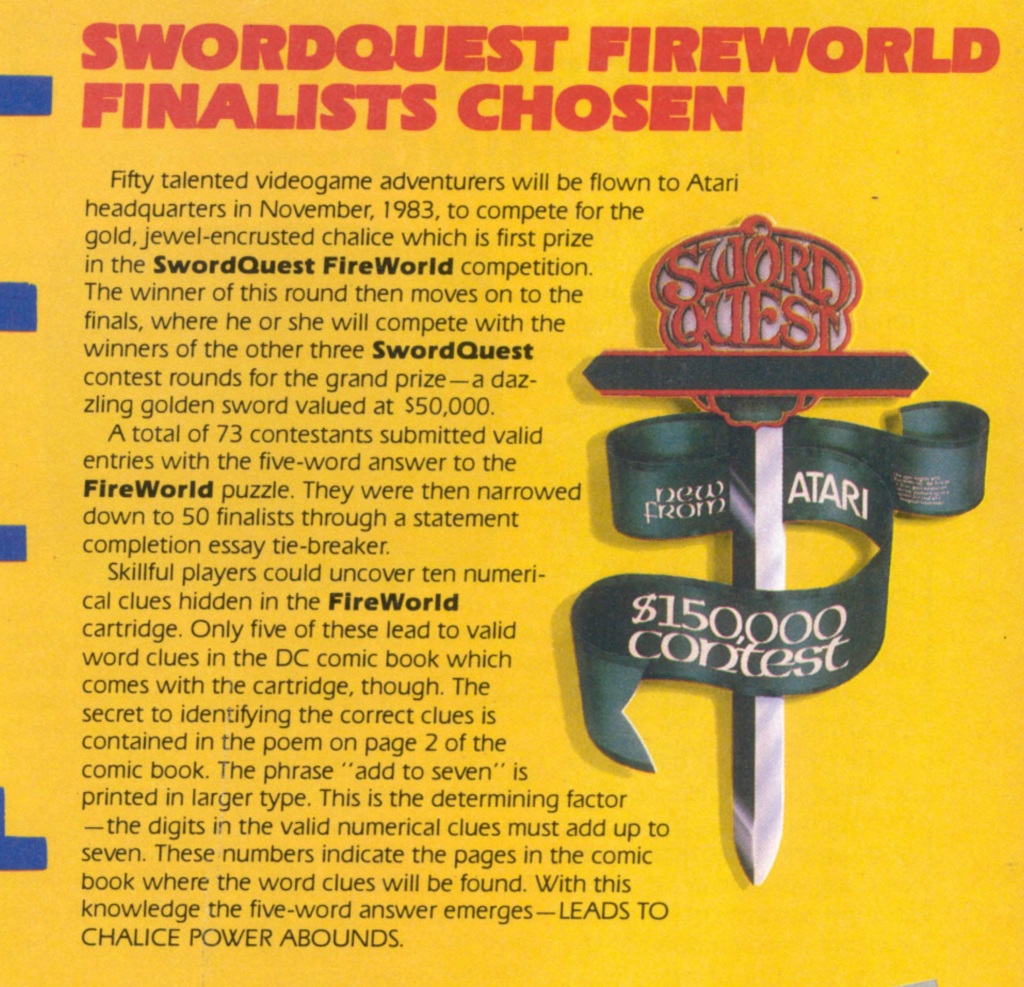

Little highlights this better than the promotion for the VCS version of Pac-Man in 1982. Atari conjured up a massive advertising campaign with a date attached to the national availability of Pac-Man for their console: April 3rd, 1982, National Pac-Man Day. They again announced their plans to port the title two months out from the date, not building a long string of anticipation (unless you were keeping an eye of the lawsuits they launched against other companies making home Pac-Man clones). However, in local retailers, that timeline of release was not enforced. A multitude of stores put the game on shelves as soon as they acquired it, causing a frenzy in some locations for customers to get the game “early”.

No company was able to follow up on the advertising promise of National Pac-Man Day. There were plenty of large advertising campaigns to try and market through the problems of the Home Video Game Crash, but none of these were planned far in advance. This may have in part been the inability of the companies to really know how long it took to bring a game to market. There wasn’t a lot of guarantees of when a cartridge would be ready for manufacturing as even when the game itself was finished it took several months to place it on store shelves. Most of all though, it simply wasn’t in the cultural consciousness to care about an unknown quantity for months outside of its release. With the exception of Star Wars as a promised trilogy building continued interest in its property, it simply wasn’t a mainstream practice.

In the post-Crash period, the advertising presence of video games became just as fragmented as it had been in the early 70s. There were more publications paying attention to video game releases and reviewing them soon after they hit store shelves without very much fanfare at all as publishers could not generally justify large advertising campaigns for the types of numbers that they did. However, interest in games often outpaced the sophistication of the companies to cater to those needs. In its place, magazine writers and editors would begin asking for more information about upcoming titles. This was especially important for series, such as Ultima. Richard Garriott started teasing Ultima IV right after Ultima III was released, promising improvements on a massive scale. The game took over two years to release as well, one of the most high-profile developments of its time.

Publications also started to proposition the game studios for early looks at games which were taking ever longer in development. Having been inspired by the game-maker promotion of publishers like Activision and Electronic Arts, most magazines since the 1980s maintained at least some interest in tracking the specifics of game development rather than purely retail products. In addition to that personal interest though, it also provided them with more information to print in the days when there wasn’t much to speak about in terms of the industry. This relationship with the press being fed exclusive early looks would become an integral part of publisher PR as they started to find that the shifts in game development were creating extended periods between major products.

There were other types of delays as well, including regional delays. Europe was most familiar with this sort of lag, having to look in envy at both Japan and US exclusives in the hopes that they might be brought to more readily available platforms in their region. Awareness in the US of the distance in original releases didn’t become particularly noticed until the purposefully delayed release of Super Mario Bros. 3 was promoted through Nintendo’s myriad of advertising channels. Even that did not have a launch date though, instead dropping in the window of March 1990. It would be to their competitors that the first widescale simultaneous launch of a video game was to happen.

The Sonic 2sDay promotion was a massive logistical undertaking for Sega in 1992. Not only a controlled launch where they would hold retail stores accountable for holding the product back, but also maintaining a consistent shipment worldwide (except for Japan, who went against their plans). The original Sonic had benefitted especially in the European press from early previews which had helped cement the character as an icon in those territories. For the first time, a video game property had the heft to carry a huge, multi-national release and the press fed Sega’s marketing efforts to promote the very idea of a launch date for video games.

Similar marketing campaigns would follow from the likes of Acclaim and their Mortal Monday promotion for the hit Mortal Kombat game. Still, the hype cycle did not exist yet as a commercially viable tool. Any anticipation for games far out in the future was a result of miscalculated production schedules. Such was the case with Origin Systems’ Strike Commander, a highly anticipated spin-off of the Wing Commander series set in World War II. This product was meant to compete with the likes of the Microprose flight simulators upon announcement of the game in 1991, but the game hit the shelves in 1993.

These disappointments would become more and more frequent for avid game purchasers paying attention to development from the magazines. The period of the 1990s became one of publishers no longer being able to predict the length of a game’s development. With the base technology moving so rapidly – especially into the uncharted realm of 3D – holding flagship games up to the standards of the market often meant that projects started to slip. Not wanting this to become apparent as a flaw in their process, publishers had more incentive to embrace previews and building the anticipation for future titles into their marketing.

At first, players did not respond well to this knowledge of extended product development. Early UseNet forum users admonished any developer who took several years to make a game. It was beyond comprehension that any game, no matter how grand, was subject to such long periods of development. Nobody had ever heard of such a thing, even though many of the great, groundbreaking experiences had taken as much time. Elite, The Legend of Zelda, Street Fighter II, and Doom had all taken well over a year from concept to fruition. They hadn’t heard of that though. In this new open age of information and communication with developers, players were making their voices known. They didn’t know why when a game looked ready enough in previews that they couldn’t expect it sooner.

At Origin Systems, Strike Commander was compounded by the epic length (and budget) development of Wing Commander III. While the game had been well received, the somewhat tortured development had fostered a notion of development perfection. One of the lead designers on Wing Commander II, Stephen Beeman (now Siobhan Beeman), adopted a phrase by which to express the difficulties of modern development, “A game is only late until it ships, but it’s bad forever.” By this, she meant to communicate that frustration with a game’s delay to say that development time was there for a reason. Being tardy was far less important than being ready, and the debate over how long it took to make a game was ultimately meaningless once the game arrived. If it was good, did development circumstances even matter?

Beeman’s words slowly resonated throughout the industry as a common response to the questions about development times, perhaps not just to their audience but also to the publishers themselves. It was heard often enough around the industry that by 1997 one journalist referred to it as a common colloquial saying. Variations of the idea became common in reporting highly anticipated titles, including that of the most highly hyped game of that era, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. A report in Edge magazine tied the phrase to Nintendo without attributing it to them, over time gradually morphing the phrase to have been the progeny of Nintendo’s famous game designer and producer, Shigeru Miyamoto. Despite other comments on delayed games, it does not appear that Miyamoto ever actually uttered these words, but they became symbolic of a new era of hype which Nintendo appeared to exemplify more and more frequently as the years went on.

By the late 90s, with the speed of information and a fully developed video game industry, the nature of releases had definitively changed. The majority of console games had a release date, relationships having been built with retailers to not try to one up their competitors by releasing stock early. This consistency would later be adopted by consumer technology companies like Apple to create an event out of every release without having to do much advertising other than setting a date. There was a difference though in that companies would not promote the upcoming titles within retail stores, only disseminating information through their official channels of communication. One last change was needed to make the wait for games part of the average consumer’s product cycle.

When the E3 conference was first established, it was an industry event meant primarily for professionals across the industry to meet and make deals. The component of previews carried over from CES had existed primarily for distributors to view upcoming titles to create excitement for their product catalog. Of course press would report on these moves, but as venerated as moments like the “two ninety-nine” speech from Sony were to those there in the moment, these marketing moves were not directed at a general audience. No publisher was viewing E3 as a way to communicate with the broader public. Any marketing they gained from it was incidental.

This changed almost immediately after the media event that was the launch of the Xbox in 2001. The well-covered and organized entry of the newest competitor in the console market made people hungry to watch the war unfold, therefore at the following E3 the materials started to become more audience-directed. Dramatic reveals such as that which Sony had given the reveal of PlayStation 2 at Tokyo Game Show were one thing, but it was quite different when at Nintendo’s press conference that year they had a live demonstration of Super Mario Sunshine and The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker by Miyamoto himself. This was appealing directly to the people at home who were familiar with the often staged nature of previews and desired to see what a game truly played like. Both Nintendo and Microsoft would disseminate materials from the show floor officially for the first time and the TV channel G4 began to hype up the show itself as a destination.

Technology has only deepened the audience’s connection with the game development process. For good and ill, it has become normal to know about a far-coming release from the moment of serious development. Teaser trailers ignite great online debate about the potential for a future title. This hype cycle is embedded within gaming culture, drawn from a past of barely sophisticated retail sales that couldn’t even blanket the country – much less the world – with product once it was available.

What to take away from this extended examination of game releases is the nature of how games were viewed prior to the modern era. Entertainment which people could own was treated mostly as an infrequent commodity prior to the confidence of companies to coordinate wide releases. Retail stores used to play a much more prominent role in making consumers aware of available games without actually assuming any active role within the marketing itself. Therefore, waiting and watching a game eagerly through its production phase was an exception rather than the rule. It’s a wonder we have as much contemporaneous development information as we do, for it was not a focus of reporting until it was incentivized by the audience’s voracious appetite for the subject.

As to the famous quote which kickstarted this whole article, we can see it in a different light now that we have a greater view of how users interacted with new games in the distant past. The notion of strong feelings about delays over games was borne specifically out of the circumstances of the mid-90s and the increasing sophistication in marketing efforts by video game publishers to enhance their advertising presence. What began as a natural outgrowth of consumer interest in the process of making video games has become integral to the cycle around video game releases. From Pac-Man, to Wing Commander, to Zelda, the pervasive reach of hype culture guides game coverage of new titles like Elden Ring. The gaming culture we live in today is fundamentally different than that of the 80s and 90s.

Special thanks to Kate Willaert for discovering the Siobhan Beeman quote!

4 thoughts on “Miyamoto’s Quote, Pac-Man, E3, and the Role of Hype Culture in Video Game History”