(20 years ago, November 30th, 1998, Looking Glass Studios under publisher Eidos Interactive released Thief: the Dark Project. This hugely influential stealth game came on the heels of one of the most complicated and innovative development periods in the history of the industry. This article tells the story of the project from the developers’ perspectives, using interviews throughout the years to craft a narrative of design focus, studio turmoil, and perseverance which encapsulates all that was great about Looking Glass. Please enjoy!)

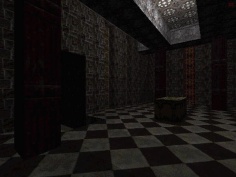

The games Looking Glass had done up to then, System Shock and Terra Nova and earlier games, used a world divided up into a grid. We all wanted to break free from that. I came up with a strategy using a technology known as “portals” to us to have more flexible world layout and be fully 3D. I put this in a tech demo named “Portal”, probably soon after Terra Nova shipped (but I don’t know for sure). […]

The games Looking Glass had done up to then, System Shock and Terra Nova and earlier games, used a world divided up into a grid. We all wanted to break free from that. I came up with a strategy using a technology known as “portals” to us to have more flexible world layout and be fully 3D. I put this in a tech demo named “Portal”, probably soon after Terra Nova shipped (but I don’t know for sure). […]

It was still an open question how to let designers *build* those worlds with as little pain as possible. I heard that John Carmack was using CSG [constructive solid geometry] to tackle the same problem for the Quake engine, which was being developed around the same time. At first this seemed really problematic to me – there were a lot of things that seemed they’d be hard to do properly, but after some email clarifications from him, I went ahead and gave it a try. I implemented a basic “CSG brush” system and a “compiler” that turned the CSG brushes into a “portal” level. I also created a brush editor, which eventually turned into DromEd. […]

Doug Church and I then created a test “level” to validate that the CSG brush idea would be viable — would let designers create interesting and functional levels. Once we saw that it worked, the project rolled forward. –Sean Barrett (2009)

I saw an ad for Looking Glass – which is a company I loved, I adored Looking Glass – for a job there as a game designer. I’m like, “I’ll do that!” Surprising to me – I didn’t really have any real qualifications – they ended up flying me up there for an interview and then they ended up hiring me. I was so thrilled. […]

I saw an ad for Looking Glass – which is a company I loved, I adored Looking Glass – for a job there as a game designer. I’m like, “I’ll do that!” Surprising to me – I didn’t really have any real qualifications – they ended up flying me up there for an interview and then they ended up hiring me. I was so thrilled. […]

About a week after I was there, somebody said “Okay, we want you to spend time working with Doug Church on this new thing,” which at the time was just called “Action-RPG”. They just had these vague titles for things. […]

I met Doug and I was a big fan of his work. Sort of like being put in the same room with Spielberg in your first week, with no experience of any kind. He was very generous. He did not treat me like a useless slob, which he probably should have. What did I know? But he was very collaborative and we just started talking about what we wanted to do. –Ken Levine (2011)

The Thief team wanted to create a first-person game that provided a totally different gaming experience, yet appealed to the existing first-person action market. –Tom Leonard (1999)

The Thief team wanted to create a first-person game that provided a totally different gaming experience, yet appealed to the existing first-person action market. –Tom Leonard (1999)

One of my responsibilities was to come up with the world and what the aesthetic was. First I came up with something called “School for Wizards”. Then I came up with something called “Dark Elves Must Die”. Then I came up with something called “Better Red than Undead”. –Ken Levine (2011)

In terms of fiction and structure. We had a post-Cold War zombies proposal called Better Red than Undead in which you were fighting off zombies in a communist Cold War era and running around and having different groups — communist spies and communist government and Western government and all these different spy groups. Meanwhile, the zombies were trying to take everyone over so you had to pick which groups you were going to ally with and go against while everyone had this common enemy of the zombies.

In terms of fiction and structure. We had a post-Cold War zombies proposal called Better Red than Undead in which you were fighting off zombies in a communist Cold War era and running around and having different groups — communist spies and communist government and Western government and all these different spy groups. Meanwhile, the zombies were trying to take everyone over so you had to pick which groups you were going to ally with and go against while everyone had this common enemy of the zombies.

But of course no one gets along so you had to play this delicate game of getting everyone on your side or enough people on your side to get the job done. -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

It was a goofy, 1950’s pulp story. At this point, Doug and I wanted it to be a sword fighting simulator. You were a character who was this CIA agent – it was sort of a campy story – you were fighting communists in Russia, there was also a zombie thing going on there. –Ken Levine (2011)

It was a goofy, 1950’s pulp story. At this point, Doug and I wanted it to be a sword fighting simulator. You were a character who was this CIA agent – it was sort of a campy story – you were fighting communists in Russia, there was also a zombie thing going on there. –Ken Levine (2011)

The premise [of Red] was that zombies were basically immune to bullets, so you had to hack them up with swords. –Marc LeBlanc (2013)

The premise [of Red] was that zombies were basically immune to bullets, so you had to hack them up with swords. –Marc LeBlanc (2013)

We had conceived of factions of people in the world being a better foil for the player because you can interact with a group in a slightly more iconic and abstract way than you can interact with an individual. Because someone can come and say, “I speak for these people and we think you’re a bad guy” or whatever. And they can do that in a way that’s a little less personal and direct and therefore has a little less requirement on the AI and conversation engine. It was this idea of having factions who you could ally with or oppose yourself with or do things for or not. -Doug Church (2005)

We had conceived of factions of people in the world being a better foil for the player because you can interact with a group in a slightly more iconic and abstract way than you can interact with an individual. Because someone can come and say, “I speak for these people and we think you’re a bad guy” or whatever. And they can do that in a way that’s a little less personal and direct and therefore has a little less requirement on the AI and conversation engine. It was this idea of having factions who you could ally with or oppose yourself with or do things for or not. -Doug Church (2005)

I think there are people who want to join teams and people who don’t and people who are opposed to being on teams. I’ve always been the sort of “I’m not on a team” kind of guy, but I’m fascinated by teams. –Ken Levine (2011)

I think there are people who want to join teams and people who don’t and people who are opposed to being on teams. I’ve always been the sort of “I’m not on a team” kind of guy, but I’m fascinated by teams. –Ken Levine (2011)

The executive team decided Red was too quirky an idea. They had no idea how to market it and they wanted something where the sword-fighting made more intrinsic sense, rather than a fictional contrivance. –Marc LeBlanc (2013)

The executive team decided Red was too quirky an idea. They had no idea how to market it and they wanted something where the sword-fighting made more intrinsic sense, rather than a fictional contrivance. –Marc LeBlanc (2013)

I definitely wrote a bunch of documents. We were doing mission breakouts and stuff like that, but it was relatively early in the process. They killed it. They didn’t kill “Action-RPG”, they just said “This idea is too far out there”. And they were probably right. –Ken Levine (2011)

I definitely wrote a bunch of documents. We were doing mission breakouts and stuff like that, but it was relatively early in the process. They killed it. They didn’t kill “Action-RPG”, they just said “This idea is too far out there”. And they were probably right. –Ken Levine (2011)

It became Dark Camelot, which was our reverse Arthurian fiction where King Arthur was a bad guy, and Merlin was this time traveller from the future and you were Mordred the black knight trying to save the setting. And Guinevere was a cool butch dyke. –Doug Church (Gillen 2005)

It became Dark Camelot, which was our reverse Arthurian fiction where King Arthur was a bad guy, and Merlin was this time traveller from the future and you were Mordred the black knight trying to save the setting. And Guinevere was a cool butch dyke. –Doug Church (Gillen 2005)

The idea was that the victors wrote the history and actually Arthur was an asshole. You and Morgana were actually sympathetic heroes, and actually you were […] African. Part of the reason they were being treated the way they were was sort of the whole racial thing. –Ken Levine (2011)

The idea was that the victors wrote the history and actually Arthur was an asshole. You and Morgana were actually sympathetic heroes, and actually you were […] African. Part of the reason they were being treated the way they were was sort of the whole racial thing. –Ken Levine (2011)

Your advisor [sic] was Morgan le Fey, who was sort of a good person. Lancelot was this evil jerk and Merlin was a time-traveling marketing guy from the future. All the Knights of the Round Table wore jerseys with logos and numbers, and the Holy Grail was this fake thing that they didn’t think existed but they were using it as a way to continue to oppress the masses and take all their money and treat them poorly. The excuse was that they needed all the money to go find the Holy Grail and they’d just sit around and have parties.

Your advisor [sic] was Morgan le Fey, who was sort of a good person. Lancelot was this evil jerk and Merlin was a time-traveling marketing guy from the future. All the Knights of the Round Table wore jerseys with logos and numbers, and the Holy Grail was this fake thing that they didn’t think existed but they were using it as a way to continue to oppress the masses and take all their money and treat them poorly. The excuse was that they needed all the money to go find the Holy Grail and they’d just sit around and have parties.

So you as the Black Knight had to break into Camelot. -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

The world was more modern than the traditional Arthurian elements. Steampunkish, but with no gunpowder. I remember seeing sketches of Merlin with a top hat, and there was talk of Knights covered in corporate logos like NASCAR drivers… We didn’t want to be straight up orcs and elves; we wanted to build something unique and memorable. Something we could own. –Marc LeBlanc (2013)

The world was more modern than the traditional Arthurian elements. Steampunkish, but with no gunpowder. I remember seeing sketches of Merlin with a top hat, and there was talk of Knights covered in corporate logos like NASCAR drivers… We didn’t want to be straight up orcs and elves; we wanted to build something unique and memorable. Something we could own. –Marc LeBlanc (2013)

Ken Levine was writing and designing for it at the time, and I seem to remember that he and Tim Stellmach were referencing more and more 30’s pulp material, which was the root of the pseudo-modernization of the setting. Lot’s of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser being passed around. –Daniel Thron (2009)

Ken Levine was writing and designing for it at the time, and I seem to remember that he and Tim Stellmach were referencing more and more 30’s pulp material, which was the root of the pseudo-modernization of the setting. Lot’s of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser being passed around. –Daniel Thron (2009)

As Mordred, you’ll fight to break the yoke of the tyrant king and set your people free. Your quest will lead you through dark crypts and creature-filled catacombs, battling Arthur’s most famous knights and Merlin’s unspeakable creations. –Looking Glass (1996)

We wanted to make a story-driven game, but action-orientated — but the more we worked on it, the more the other ideas weren’t quite working out. It was a more organic approach than Underworld and Shock. –Doug Church (Gillen 2005)

We wanted to make a story-driven game, but action-orientated — but the more we worked on it, the more the other ideas weren’t quite working out. It was a more organic approach than Underworld and Shock. –Doug Church (Gillen 2005)

The missions that we had the best definition on and the best detail on were all the breaking into Camelot, meeting up with someone, getting a clue, stealing something, whatever. As we did more work in that direction, and those continued to be the missions that we could explain best to other people, it just started going that way. -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

The thing that remained throughout almost the entire product is we always wanted to have AIs who when you were walking around a corridor would say, ‘Hey, is somebody there?’ That’s a concept we had almost from the very beginning. All those ideas, the AI would have a state beyond ‘I see you’ or ‘I don’t see you’, ‘I’m attacking you’ or ‘I have no idea you exist’.

The thing that remained throughout almost the entire product is we always wanted to have AIs who when you were walking around a corridor would say, ‘Hey, is somebody there?’ That’s a concept we had almost from the very beginning. All those ideas, the AI would have a state beyond ‘I see you’ or ‘I don’t see you’, ‘I’m attacking you’ or ‘I have no idea you exist’.

The actual “It’s going to be a game about a thief” idea came from Paul Neurath. –Ken Levine (2011)

Stealth hadn’t been core to our thinking, but we started to bounce other concepts around and stealth came up. And then the obvious thing to us was, “Well, let’s play in the role of a thief.” We want a more singular experience that’s focused on a role. We know what thieves do. Players know what thieves do. It creates an immediate context, which is especially important if you’re doing an innovative game. –Paul Neurath (2018)

Stealth hadn’t been core to our thinking, but we started to bounce other concepts around and stealth came up. And then the obvious thing to us was, “Well, let’s play in the role of a thief.” We want a more singular experience that’s focused on a role. We know what thieves do. Players know what thieves do. It creates an immediate context, which is especially important if you’re doing an innovative game. –Paul Neurath (2018)

We were still struggling with Dark Camelot – he said, “Why don’t we make it a game about a thief?” I think I liked that idea, I don’t know if Doug liked that idea from the outset. I think he grew to like it. […] Doug asked me to start thinking about what that would be like systemically. He and I talked a lot about it. –Ken Levine (2011)

We were still struggling with Dark Camelot – he said, “Why don’t we make it a game about a thief?” I think I liked that idea, I don’t know if Doug liked that idea from the outset. I think he grew to like it. […] Doug asked me to start thinking about what that would be like systemically. He and I talked a lot about it. –Ken Levine (2011)

Paul had been pushing for a while that the thief side of it was the really interesting part and why not you just do a thief game. And as things got more chaotic and more stuff was going on and we were having more issues with how to market the stuff, we just kept focusing in on the thief part. -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

Paul had been pushing for a while that the thief side of it was the really interesting part and why not you just do a thief game. And as things got more chaotic and more stuff was going on and we were having more issues with how to market the stuff, we just kept focusing in on the thief part. -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

All that was really retained from [Dark Camelot] was the idea of the player character as [a] less sort of black and white hero and a more kind of Robin Hood figure. –Tim Stellmach (2011)

I started thinking about submarine games and stealth fighter games because that was very similar. How powerful you are when you are unseen and how weak you are when you are spotted. […] In a submarine there are layers in the water of different temperatures, very cold water and warm water, and because […] of the density of cold water versus hot water they form pockets, and those are called thermocline layers. Submarines will often go through those and form a barrier sonar. That gives the ocean a geography and terrain.

I started thinking about submarine games and stealth fighter games because that was very similar. How powerful you are when you are unseen and how weak you are when you are spotted. […] In a submarine there are layers in the water of different temperatures, very cold water and warm water, and because […] of the density of cold water versus hot water they form pockets, and those are called thermocline layers. Submarines will often go through those and form a barrier sonar. That gives the ocean a geography and terrain.

I started thinking about how do we build a terrain that’s based upon sound and visuals. I was originally thinking about sound in particular. –Ken Levine (2011)

Sound plays a more central role in Thief than in any other game I can name. Project Director Greg LoPiccolo had a vision of Thief that included a rich aural environment where sound both enriched the environment and was an integral part of gameplay. The team believed in and achieved this vision, and special credit goes to audio designer Eric Brosius. –Tom Leonard (1999)

Sound plays a more central role in Thief than in any other game I can name. Project Director Greg LoPiccolo had a vision of Thief that included a rich aural environment where sound both enriched the environment and was an integral part of gameplay. The team believed in and achieved this vision, and special credit goes to audio designer Eric Brosius. –Tom Leonard (1999)

I think one of the ways Looking Glass was fairly forward thinking was that they brought people in-house – so you can live with the game and absorb the game – and then took the step to put a lot of the integration abilities into non-coder’s hands. I didn’t know how to code. In Terra Nova I remember taking stuff, have to walk over to the programmer I was working with, “Okay, now do this. Oh, don’t play that.” It had no control over volume or panning or anything. […]

I think one of the ways Looking Glass was fairly forward thinking was that they brought people in-house – so you can live with the game and absorb the game – and then took the step to put a lot of the integration abilities into non-coder’s hands. I didn’t know how to code. In Terra Nova I remember taking stuff, have to walk over to the programmer I was working with, “Okay, now do this. Oh, don’t play that.” It had no control over volume or panning or anything. […]

In Thief we developed a whole text file-based editing system. –Eric Brosius (2011)

One of the development goals for the Dark Engine, on which Thief is built, was to create a set of tools that enabled programmers, artists, and designers to work more effectively and independently. The focus of this effort was to make the game highly data-driven and give non-programmers a high degree of control over the integration of their work.

One of the development goals for the Dark Engine, on which Thief is built, was to create a set of tools that enabled programmers, artists, and designers to work more effectively and independently. The focus of this effort was to make the game highly data-driven and give non-programmers a high degree of control over the integration of their work.

Primarily designed by programmer Marc “Mahk” LeBlanc, the Object System was a general database for managing the individual objects in a simulation. It provided a generic notion of properties that an object might possess, and relations that might exist between two objects. –Tom Leonard (1999)

Anytime something happened in the game, it would spit out an event to the audio engine. Then we could basically make up any names for tags. We could tag any item with something like this. Once they did that, I could go in and add in all the footstep sounds myself. […] Every time something was drawn they would send a Create event to the sound system and I could choose whether I wanted to hook something up to it. There was just this giant database [to] look up an event and a series of tags, if something matched it would play a sound. […]

Anytime something happened in the game, it would spit out an event to the audio engine. Then we could basically make up any names for tags. We could tag any item with something like this. Once they did that, I could go in and add in all the footstep sounds myself. […] Every time something was drawn they would send a Create event to the sound system and I could choose whether I wanted to hook something up to it. There was just this giant database [to] look up an event and a series of tags, if something matched it would play a sound. […]

I also did a lot of stuff like making test levels. I would build myself a room that was 20 foot by 20 foot with all the textures that the game has, with all the styles. Here’s the gravel, and here’s the sand, and here’s the grass, and here’s the rock, and here’s the marble. I could bring crates in there and after we hook up sounds to the physics, I’d throw them around and test them. This was like a virtual foley studio. –Eric Brosius (2011)

I was so taken by the digital audio from System Shock 1. As crude as the graphics were, the audio was so evolved already once you had digital audio. It’s just recording stuff. You had guys like Eric Brosius and Kemal [Amarasingham] and Greg LoPiccolo who were so good at doing audio and ambient beds that Looking Glass audio was so far ahead of everything else. […] It was such a powerful tool, we really wanted to exploit that. –Ken Levine (2011)

I was so taken by the digital audio from System Shock 1. As crude as the graphics were, the audio was so evolved already once you had digital audio. It’s just recording stuff. You had guys like Eric Brosius and Kemal [Amarasingham] and Greg LoPiccolo who were so good at doing audio and ambient beds that Looking Glass audio was so far ahead of everything else. […] It was such a powerful tool, we really wanted to exploit that. –Ken Levine (2011)

When constructing a Thief mission, designers built a secondary “room database” that reflected the connectivity of spaces at a higher level than raw geometry. Although this was also used for script triggers and AI optimizations, the primary role of the room database was to provide a representation of the world simple enough to allow realistic real-time propagation of sounds through the spaces. –Tom Leonard (1999)

When constructing a Thief mission, designers built a secondary “room database” that reflected the connectivity of spaces at a higher level than raw geometry. Although this was also used for script triggers and AI optimizations, the primary role of the room database was to provide a representation of the world simple enough to allow realistic real-time propagation of sounds through the spaces. –Tom Leonard (1999)

The fact that our sound propagation in Thief was so good [is] because we did not want to deceive you about where things that you were hearing were. There was a lot of work put in to making the sound propagation quite naturalistic. So sound would propagate properly through doorways and not through solid walls and stuff. Because of that, we had all this data and we could attenuate sound when there was a closed door so that wouldn’t fool you. –Tim Stellmach (2011)

The fact that our sound propagation in Thief was so good [is] because we did not want to deceive you about where things that you were hearing were. There was a lot of work put in to making the sound propagation quite naturalistic. So sound would propagate properly through doorways and not through solid walls and stuff. Because of that, we had all this data and we could attenuate sound when there was a closed door so that wouldn’t fool you. –Tim Stellmach (2011)

Sound is now appearing in the game, hooked up to the AI. Hurrahs to Eric and Briscoe [Rogers]. Guards now hum, mumble, and otherwise talk to themselves as they patrol about (this is important, so that you can hear them coming and plan accordingly.)

The guards also react to you as you move around; if they only sort of detect you, they’ll mutter something like “what was that?”, and make sharper shouts up to when they detect you and raise the hue and cry. 1997-02-26 Looking Glass Project Diary

Other companies limit themselves to brutal action and bloodshed. There is no consideration, the actions have no consequences, the world does not change permanently by the actions of the player. We have a higher claim. In The Dark Project, the game world will be populated by people who respond differently to decent people compared to someone who has killed a baby. –Warren Spector (Power Play 1997-03)

Other companies limit themselves to brutal action and bloodshed. There is no consideration, the actions have no consequences, the world does not change permanently by the actions of the player. We have a higher claim. In The Dark Project, the game world will be populated by people who respond differently to decent people compared to someone who has killed a baby. –Warren Spector (Power Play 1997-03)

It’s not like Duke Nukem where you have lots and lots of firepower. It’s more like you’re smart, and get smarter through the course of the game.

It’s not like Duke Nukem where you have lots and lots of firepower. It’s more like you’re smart, and get smarter through the course of the game.

Clearly if you want a technologically optimized, low-brain shooter, talk to iD. That’s what they do, and my guess is they’ll do it better than we ever could. –Greg LoPiccolo (1997-03 Next Generation)

A lot of the other games that were out there at that time, that were first-person games, moved really fast. They were shooters and you walked through really quickly. This was a game where you move through the environment really slowly. One of the big advantages is that it gives the player a chance to pay attention to everything that they pass by because they’re not running through shooting a giant machine gun. -Eric Brosius (2016)

A lot of the other games that were out there at that time, that were first-person games, moved really fast. They were shooters and you walked through really quickly. This was a game where you move through the environment really slowly. One of the big advantages is that it gives the player a chance to pay attention to everything that they pass by because they’re not running through shooting a giant machine gun. -Eric Brosius (2016)

We return to our “Underworld” roots, but with some changes. For one thing, we are now approaching the issue in a more mission-oriented way instead of a large, continuous world. It is not realistic to expect players to give us hundreds of hours of their lives just to explore a large, flat-bottomed world. We will give them the world in small, handy doses. By creating an environment that responds to all actions and decisions of the player, we want to go further than the other games of this kind.

We return to our “Underworld” roots, but with some changes. For one thing, we are now approaching the issue in a more mission-oriented way instead of a large, continuous world. It is not realistic to expect players to give us hundreds of hours of their lives just to explore a large, flat-bottomed world. We will give them the world in small, handy doses. By creating an environment that responds to all actions and decisions of the player, we want to go further than the other games of this kind.

The total involvement of the player in the program is one of the key philosophies at Looking Glass. –Warren Spector (Power Play 1997-03)

Essentially we’re building a type of simulator where object interactions are correct and physics are tied in correctly, but not as weak as a Daggerfall thing, where there’s zillions of NPCs in this large empty world. –Greg LoPiccolo (1997-03 Next Generation)

Essentially we’re building a type of simulator where object interactions are correct and physics are tied in correctly, but not as weak as a Daggerfall thing, where there’s zillions of NPCs in this large empty world. –Greg LoPiccolo (1997-03 Next Generation)

The game environment was developed using Looking Glass’s own technology called “Act-React.” This system allows the implementation of “intelligent objects.” The definition is basically simple; Objects in the world of Dark react to actions. Wooden objects “know” that they can burn when they are lit, water extinguishes flames, or heavy objects crush lighter objects.

These player-initiated actions have a direct bearing on the gameplay. –PC Games (1997-03)

Things that burn will burn, and then it’s up to the player to decide to burn things, whether or not we’ve anticipated it. That’s Act-React’s real strength. We’re using it for numerous game properties, including sound in the same sort of way. –Jeff Yaus (1997-03 Next Generation)

Things that burn will burn, and then it’s up to the player to decide to burn things, whether or not we’ve anticipated it. That’s Act-React’s real strength. We’re using it for numerous game properties, including sound in the same sort of way. –Jeff Yaus (1997-03 Next Generation)

Imagine a scene in which you have to get an important document from a library. Once there, you notice that an ice elemental is guarding the place. Aha! The elemental can melt with fire, but the flames set one of the books in the library on fire, which in turn ignites a table and after a while the whole locality burns. The ice elemental may be destroyed, but you will have to find another way to access the information contained in the scorched document! Connections like these are just the tip of the iceberg. –Warren Spector (Power Play 1997-03)

Imagine a scene in which you have to get an important document from a library. Once there, you notice that an ice elemental is guarding the place. Aha! The elemental can melt with fire, but the flames set one of the books in the library on fire, which in turn ignites a table and after a while the whole locality burns. The ice elemental may be destroyed, but you will have to find another way to access the information contained in the scorched document! Connections like these are just the tip of the iceberg. –Warren Spector (Power Play 1997-03)

If you fire a flame arrow into a crate, it will catch fire, and if it’s full of dynamite it will explode after it gets hot enough. Basically the world understands heat, cold, and fear, and light and dark. All of these things are expressed intuitively and everything in the world understands them. –Greg LoPiccolo (PC Games 1997)

If you fire a flame arrow into a crate, it will catch fire, and if it’s full of dynamite it will explode after it gets hot enough. Basically the world understands heat, cold, and fear, and light and dark. All of these things are expressed intuitively and everything in the world understands them. –Greg LoPiccolo (PC Games 1997)

The original concept doc for Thief had a lot more focus on the use of elementals as power sources and these sort of background elements – no pun intended – having to do with the Hammerites and their role in the world. The Trickster kind of came as counterpoint to that, in a pretty obvious way. –Tim Stellmach (2011)

The original concept doc for Thief had a lot more focus on the use of elementals as power sources and these sort of background elements – no pun intended – having to do with the Hammerites and their role in the world. The Trickster kind of came as counterpoint to that, in a pretty obvious way. –Tim Stellmach (2011)

![]()

![]()

Originally the only two forces I had at play were the Church – the Hammerites – and the Trickster. These are sort of the competing forces in the world. One was of technology and order and structure, one of chaos and nature and you were sort of caught in between them. That’s clearly a theme I tend to be drawn to. There are these powers-that-be. –Ken Levine (2011)

Originally the only two forces I had at play were the Church – the Hammerites – and the Trickster. These are sort of the competing forces in the world. One was of technology and order and structure, one of chaos and nature and you were sort of caught in between them. That’s clearly a theme I tend to be drawn to. There are these powers-that-be. –Ken Levine (2011)

Some of the propaganda stuff that you look at with the [Hammerites], we had done a lot of propaganda posters in Dark Camelot against Mordred. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Some of the propaganda stuff that you look at with the [Hammerites], we had done a lot of propaganda posters in Dark Camelot against Mordred. -Brennan Priest (2016)

It used the backdrop of an epic, but didn’t try to tell an epic. I think that’s still one of the greatest mistakes games make. They set down all the proper names then proceed to show you the conflict at a kingdom versus kingdom level. What you have to do is just set that in the back and tell the story of one character. Tell the low-level story. –Nate Wells (2010)

I wanted it to be familiar to a fantasy audience – because it’s a fantasy world – but I also wanted it to feel like a film noir. The closest analog to a thief would be like a private detective. […] I started thinking about a hybrid aesthetic which was not just ‘on the nose’ fantasy, it was more of a noir aesthetic. The steampunk-y stuff worked well with that. –Ken Levine (2011)

I wanted it to be familiar to a fantasy audience – because it’s a fantasy world – but I also wanted it to feel like a film noir. The closest analog to a thief would be like a private detective. […] I started thinking about a hybrid aesthetic which was not just ‘on the nose’ fantasy, it was more of a noir aesthetic. The steampunk-y stuff worked well with that. –Ken Levine (2011)

We held on to some early thematic constraints about the rules of magic in our world – the player’s main tools map pretty cleanly onto the Aristotelian elements of water, fire, air, and earth. But things really only needed to make sense symbolically, not realistically. -Tim Stellmach (2016)

We held on to some early thematic constraints about the rules of magic in our world – the player’s main tools map pretty cleanly onto the Aristotelian elements of water, fire, air, and earth. But things really only needed to make sense symbolically, not realistically. -Tim Stellmach (2016)

Greg LoPiccolo had a very specific look in his head of how he thought we could tell stories. Sort of like an animated collage, layered with textures and symbols that implied meaning and established the vibe of the world. We’d just done Terra Nova, which had an hour of full motion video and we knew we didn’t want to do THAT again, so we came up with something that better fit the world of Thief. Playing with shadow and texture to reveal bits of motion or story. –Josh Randall (2013)

Greg LoPiccolo had a very specific look in his head of how he thought we could tell stories. Sort of like an animated collage, layered with textures and symbols that implied meaning and established the vibe of the world. We’d just done Terra Nova, which had an hour of full motion video and we knew we didn’t want to do THAT again, so we came up with something that better fit the world of Thief. Playing with shadow and texture to reveal bits of motion or story. –Josh Randall (2013)

We had this big story to tell in Dark Camelot and I had three artists. Compared to the teams at Origin [Systems] we didn’t have the money. Our storyboard artists, our concept artists at the time really came from a comic book background. Robb Waters did a lot of comic book type stuff. X-Files had just come out. I don’t know if you’ve ever watched the intro to X-Files but there’s a lot of that are being scaled and moved around. I got the concept, the idea to go “Instead of doing this fully-rendered, full 3D cutscene let’s just do animated comic books.” -Brennan Priest (2016)

We had this big story to tell in Dark Camelot and I had three artists. Compared to the teams at Origin [Systems] we didn’t have the money. Our storyboard artists, our concept artists at the time really came from a comic book background. Robb Waters did a lot of comic book type stuff. X-Files had just come out. I don’t know if you’ve ever watched the intro to X-Files but there’s a lot of that are being scaled and moved around. I got the concept, the idea to go “Instead of doing this fully-rendered, full 3D cutscene let’s just do animated comic books.” -Brennan Priest (2016)

Danno [Dan Thron]’s been working on storyboarding of cutscenes (for both between and during missions; we’ve got some innovative video ideas). –1997-04-18 Looking Glass Project Diary

Dan Thron, when he got a hold of that concept, he actually made it beautiful. All those cutscenes that were in the original Thief, he took that concept and ran with it and made it absolutely gorgeous. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Dan Thron, when he got a hold of that concept, he actually made it beautiful. All those cutscenes that were in the original Thief, he took that concept and ran with it and made it absolutely gorgeous. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Ken and Robb were developing the cinematics when i came on board, and the first pass was designed to look like an active comic page — it was very cool looking. Then Josh Randall and I took a swing at them; he introduced me to After Effects, and once we started designing for that style of animation, the whole thing really took off — especially when Eric Brosius created such an inspiring, modern score.

Ken and Robb were developing the cinematics when i came on board, and the first pass was designed to look like an active comic page — it was very cool looking. Then Josh Randall and I took a swing at them; he introduced me to After Effects, and once we started designing for that style of animation, the whole thing really took off — especially when Eric Brosius created such an inspiring, modern score.

But to be honest, much of the stylistic darkness that became the signature look of the cinematics came from the fact that we only had so much time — and there’s nothing quicker to paint than shadows. We all had to think harder because we had such severe limitations on the production — and I think that goes for the whole of LG. –Daniel Thron (2009)

In essence you’re a thief in this undefined medieval age, sort of medieval meets Brazil meets City of Lost Children. There’s electricity, some magic, and some 19th century machinery kind of stuff. –Greg LoPiccolo (1997-03 Next Generation)

In essence you’re a thief in this undefined medieval age, sort of medieval meets Brazil meets City of Lost Children. There’s electricity, some magic, and some 19th century machinery kind of stuff. –Greg LoPiccolo (1997-03 Next Generation)

At that time, The City of Lost Children came out. It heavily, heavily influenced my art direction for Thief. -Brennan Priest (2016)

At that time, The City of Lost Children came out. It heavily, heavily influenced my art direction for Thief. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Thief’s style still looks fresh to me today; it’s one of the most original settings I’ve ever seen. […]

Thief’s style still looks fresh to me today; it’s one of the most original settings I’ve ever seen. […]

Mark Lizotte was easily the most informed in terms of art history, and he led the charge in realizing the Dickensian/Baroque mix, I think we were both in love with the idea that these styles showed the maximum possible difference between the rich and poor — the rich were ostentatious beyond reason, and the streets between their houses were something out of Oliver Twist.

I think it made the idea of being a thief seem pretty attractive I had also just read a book by Caleb Carr called ‘The Alienist,’ and the both the story and setting of that were very inspiring — but it was the cover really hooked me: it was a photo by Alfred Stieglitz — and from that, many of his shots became the source of how I thought about the City. –Daniel Thron (2009)

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco was a real keystone starting point for the feel of Thief, at least in terms of the way the world worked. -Steve Pearsall (2017)

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco was a real keystone starting point for the feel of Thief, at least in terms of the way the world worked. -Steve Pearsall (2017)

There was a Three Musketeers film that had come out at that point and there were a bunch of dungeons in it. We actually even digitized some of that and pulled our first fire animations directly from that movie. We converted the VHS to digital, I took that into PowerAnimator, then hand-painted single pixels to cut out the eight frames of flame animation. It took forever. -Brennan Priest (2016)

There was a Three Musketeers film that had come out at that point and there were a bunch of dungeons in it. We actually even digitized some of that and pulled our first fire animations directly from that movie. We converted the VHS to digital, I took that into PowerAnimator, then hand-painted single pixels to cut out the eight frames of flame animation. It took forever. -Brennan Priest (2016)

The `Project geared up for school this week as Greg and I played guinea pigs for our 3D guru’s level-building tips, covering how to keep your polygon counts low and your frame rates high. Work on actual level construction held its breath pending the outcome of this and other experiments. –Tim Stellmach (1997)

The `Project geared up for school this week as Greg and I played guinea pigs for our 3D guru’s level-building tips, covering how to keep your polygon counts low and your frame rates high. Work on actual level construction held its breath pending the outcome of this and other experiments. –Tim Stellmach (1997)

The basic core of the renderer for Thief was written in the fall of 1995 as an after-hours experiment by programmer Sean Barrett. During the following year, the renderer and geometry-editing tools were fleshed out, and with “Dark Camelot” supposed to ship some time in 1997, it looked like we would have a pretty attractive game. Then, at the end of 1996, Sean decided to leave Looking Glass. Although he periodically contracted with us to add features, and we were able to add hardware support and other minor additions, the renderer never received the attention it needed to reach the state-of-the-art in 1998. […]

The basic core of the renderer for Thief was written in the fall of 1995 as an after-hours experiment by programmer Sean Barrett. During the following year, the renderer and geometry-editing tools were fleshed out, and with “Dark Camelot” supposed to ship some time in 1997, it looked like we would have a pretty attractive game. Then, at the end of 1996, Sean decided to leave Looking Glass. Although he periodically contracted with us to add features, and we were able to add hardware support and other minor additions, the renderer never received the attention it needed to reach the state-of-the-art in 1998. […]

When the project started a few months into 1996, the avalanche of Quake licenses hadn’t really begun and Unreal was still two years away. By the time licensing was a viable choice, the game and the renderer were too tightly integrated for us to consider changing. –Tom Leonard (1999)

We still only had 256 colors at this point but I had really liked the concept we developed at Origin of using high-end renders, cutting them up, and using them as textures on low-poly stuff. As a Texas kid – I had lived in L.A, I’d lived in Purdue – but being in Boston, which was so much older, there was all this beautiful, wonderful stonework around. I bought a camera, went out, and took about 25 rolls of film of flat pictures of all these different rocks and things to bring back as textures. Brought back the photos, got them developed, brought them into a scanner (which took forever).

We still only had 256 colors at this point but I had really liked the concept we developed at Origin of using high-end renders, cutting them up, and using them as textures on low-poly stuff. As a Texas kid – I had lived in L.A, I’d lived in Purdue – but being in Boston, which was so much older, there was all this beautiful, wonderful stonework around. I bought a camera, went out, and took about 25 rolls of film of flat pictures of all these different rocks and things to bring back as textures. Brought back the photos, got them developed, brought them into a scanner (which took forever).

I had to hand scan each photograph and get them in. Then I had to run a process through PowerAnimator to get them down to 256 colors and I had to choose all those colors. All the pallets you wind up seeing in a lot of those missions in Thief, when it finally shipped, were the color pallets I created. A few of the objects I originally made were still in there as well. […] I kept a 128 which were the same in every level, then the other 128 could vary level by level so you could get some sort of variation. -Brennan Priest (2016)

My recollection is you could have about 400-500 polygons on screen at a time. You had to be crazy disciplined about your viewpoints. –Greg LoPiccolo (Dev Game Club 2018)

My recollection is you could have about 400-500 polygons on screen at a time. You had to be crazy disciplined about your viewpoints. –Greg LoPiccolo (Dev Game Club 2018)

I remember Greg LoPiccolo coming to me and I think my restriction [for characters] was something like 160 polygons or something ridiculous, maybe it was like 200. Then, at the last hour, Greg comes around and says they had to be like 100 polygons. So I’m just scrutinizing these things and collapsing it. –Robb Waters (2010)

I remember Greg LoPiccolo coming to me and I think my restriction [for characters] was something like 160 polygons or something ridiculous, maybe it was like 200. Then, at the last hour, Greg comes around and says they had to be like 100 polygons. So I’m just scrutinizing these things and collapsing it. –Robb Waters (2010)

Robb finally showed off a bunch of creature models at a much-belated review, and now everyone worships at his sandalled feet. Robb also did almost all the creatures for System Shock, so it’s not like anyone’s surprised. –1997-10-10 Looking Glass Project Diary

My real first task as art director on Dark Camelot was to take a bunch of mo-cap data that they had already gotten and get that into 3D Studio. -Brennan Priest (2016)

My real first task as art director on Dark Camelot was to take a bunch of mo-cap data that they had already gotten and get that into 3D Studio. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Our first motion capture shoot went off without a hitch this week. We got an even 100 short animation scenes shot in one hectic day. Jonathan [Chey], our model, is a sword and bow enthusiast himself and ad-libbed some lovely sword kata at the shoot. Now comes the long process of sifting through and editing the animation data. –1997-03-28 Looking Glass Project Diary

We originally motion captured all sorts of stabbing and chopping and slashings but when you take just the arm part of that motion and try to play it, try to imagine stabbing someone or chopping someone if the rest of your torso is bolted into a frame. You’re a wussy. […] We ended up ripping out all the motion capture cuz that just wasn’t working. –Laura Baldwin (2011)

We originally motion captured all sorts of stabbing and chopping and slashings but when you take just the arm part of that motion and try to play it, try to imagine stabbing someone or chopping someone if the rest of your torso is bolted into a frame. You’re a wussy. […] We ended up ripping out all the motion capture cuz that just wasn’t working. –Laura Baldwin (2011)

I originally started working on trying to do the sword fighting, because the idea was you would move the mouse and it would move your arm and you would try to swordfight that way. You actually had to make each movement with the mouse as if you were parrying or thrusting. That was overly complicated and we were having a real difficult time with it. -Brennan Priest (2016)

I originally started working on trying to do the sword fighting, because the idea was you would move the mouse and it would move your arm and you would try to swordfight that way. You actually had to make each movement with the mouse as if you were parrying or thrusting. That was overly complicated and we were having a real difficult time with it. -Brennan Priest (2016)

We moved away from a direct analog control of [swordfighting]. In first-person we just could never get that working well. I remember being heartbroken when Doug as just like “I just don’t think this is going to work” because he had prototyped some of it. […] He was right, I’m sure, because you just don’t have that much 3D perception right in front of you. –Ken Levine (2011)

We moved away from a direct analog control of [swordfighting]. In first-person we just could never get that working well. I remember being heartbroken when Doug as just like “I just don’t think this is going to work” because he had prototyped some of it. […] He was right, I’m sure, because you just don’t have that much 3D perception right in front of you. –Ken Levine (2011)

One of the fundamentals of Looking Glass is that the game design ruled the roost. The engine was a tool to be used by the designers to create the game. A lot of the flashiest games in that era were very simple games with neat graphics engines; it often seemed like the game was designed to work off the limitations of the engine and to show it the graphics off in the best light.

One of the fundamentals of Looking Glass is that the game design ruled the roost. The engine was a tool to be used by the designers to create the game. A lot of the flashiest games in that era were very simple games with neat graphics engines; it often seemed like the game was designed to work off the limitations of the engine and to show it the graphics off in the best light.

That never happened at Looking Glass; designers did what they were going to do, and it was the job of the engine to make it possible. –Sean Barrett (2009)

As the lighting got in, it became more obvious that we could play on light and shadow better than anybody else had ever really done. -Brennan Priest (2016)

As the lighting got in, it became more obvious that we could play on light and shadow better than anybody else had ever really done. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Much of the actual gameplay will involve using shadows effectively. You’re constantly sneaking around and making decisions: Who to kill, who to sneak past, and who to trick. –Greg LoPiccolo (1997-03 Next Generation)

Much of the actual gameplay will involve using shadows effectively. You’re constantly sneaking around and making decisions: Who to kill, who to sneak past, and who to trick. –Greg LoPiccolo (1997-03 Next Generation)

The original engine didn’t have lightmapping, and after the Quake demo came out we quickly agreed I had to copy it for The Dark Project. –Sean Barrett (2009)

The original engine didn’t have lightmapping, and after the Quake demo came out we quickly agreed I had to copy it for The Dark Project. –Sean Barrett (2009)

When the game lighting system came in, we found the game was just really dark. My callsign at the time was ‘Dark Priest’ (it still is), I’m setting the art direction, and we just started calling it ‘The Dark Project’. -Brennan Priest (2016)

When the game lighting system came in, we found the game was just really dark. My callsign at the time was ‘Dark Priest’ (it still is), I’m setting the art direction, and we just started calling it ‘The Dark Project’. -Brennan Priest (2016)

I left Origin to make games like this. It may look similar to other games, but we’re after a different simulation. –Warren Spector (1997-03 Next Generation)

I left Origin to make games like this. It may look similar to other games, but we’re after a different simulation. –Warren Spector (1997-03 Next Generation)

Warren’s fervor and enthusiasm are priceless, we work very closely together, and the man knows more about computer games than anyone else. In addition, I agree with his design philosophy hundred-pronged. Warren believes that there are different solutions to each task in the game and in life. A game can not be restrictive and limit the imagination, because there is only one way to solve a puzzle. –Greg LoPiccolo (PC Games 1997-03)

Warren’s fervor and enthusiasm are priceless, we work very closely together, and the man knows more about computer games than anyone else. In addition, I agree with his design philosophy hundred-pronged. Warren believes that there are different solutions to each task in the game and in life. A game can not be restrictive and limit the imagination, because there is only one way to solve a puzzle. –Greg LoPiccolo (PC Games 1997-03)

It’s not actually possible to know exactly what you want to do from the beginning, so you have to be able to grip the problem as you go along, and adapt your plan. […] Can you design more than one solution? Could you enrich your game by making an environment in which the player can experiment and improvise? -Tim Stellmach (2000)

It’s not actually possible to know exactly what you want to do from the beginning, so you have to be able to grip the problem as you go along, and adapt your plan. […] Can you design more than one solution? Could you enrich your game by making an environment in which the player can experiment and improvise? -Tim Stellmach (2000)

There’s no question that we were always about maximizing the player choice as much as possible and I think that in Underworld in particular we had a lot of watching people do things we hadn’t expected or be clever in ways we hadn’t expected. […] So in Thief, though obviously it was a much more focused game, we wanted to keep that sense of do whatever you want to do and do it however you want to do it so you can kill people or not, you can try to evade them or take them out, you can use your gear to sneak around or you can go straight in the front.

There’s no question that we were always about maximizing the player choice as much as possible and I think that in Underworld in particular we had a lot of watching people do things we hadn’t expected or be clever in ways we hadn’t expected. […] So in Thief, though obviously it was a much more focused game, we wanted to keep that sense of do whatever you want to do and do it however you want to do it so you can kill people or not, you can try to evade them or take them out, you can use your gear to sneak around or you can go straight in the front.

We very consciously wanted to maximize the players’ ability to do it their own way. -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

The thing that worked really well for me, and is maybe even closer to the Looking Glass philosophy, is player expression and freedom. The fact that it’s not a game that they insist you approach it in one way. There’s always a certain amount of choice that you’re making, choice that has consequence, a tactical expression you might make about how you want to deal with the challenges. Just in general, there’s always the sense that it’s your game. –Randy Smith (2011)

The thing that worked really well for me, and is maybe even closer to the Looking Glass philosophy, is player expression and freedom. The fact that it’s not a game that they insist you approach it in one way. There’s always a certain amount of choice that you’re making, choice that has consequence, a tactical expression you might make about how you want to deal with the challenges. Just in general, there’s always the sense that it’s your game. –Randy Smith (2011)

There are sure to be some changes to its release in the fourth quarter of this year. It certainly seems obvious now that Dark will bring fresh wind into the neglected RPG genre. –PC Games (1997-03)

Within the first couple of months of being there, I had to lay off some people. I found it interesting that they gave me that job and I figured it out later. “The art director at the time was really good friends with all these people and having a hard time.” So here I am, this is my second real job in the industry. I am an art director and therefore a manager but I’m two months in and I’m having to lay off people. That was really hard. It didn’t leave a bad taste in my mouth, but it meant that we were working on The Dark Project and it looked like pretty dark times for Looking Glass. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Within the first couple of months of being there, I had to lay off some people. I found it interesting that they gave me that job and I figured it out later. “The art director at the time was really good friends with all these people and having a hard time.” So here I am, this is my second real job in the industry. I am an art director and therefore a manager but I’m two months in and I’m having to lay off people. That was really hard. It didn’t leave a bad taste in my mouth, but it meant that we were working on The Dark Project and it looked like pretty dark times for Looking Glass. -Brennan Priest (2016)

The company shed half of its staff in a span of six months, and while the active teams tried to stay focused, it was hard when one day the plants were gone, another day the coffee machine, then the water cooler. […] When we were forced to close our Austin office, we lost our producer, Warren Spector, as well as some programmers who made valuable technology contributions to our engine. –Tom Leonard (1999)

The company shed half of its staff in a span of six months, and while the active teams tried to stay focused, it was hard when one day the plants were gone, another day the coffee machine, then the water cooler. […] When we were forced to close our Austin office, we lost our producer, Warren Spector, as well as some programmers who made valuable technology contributions to our engine. –Tom Leonard (1999)

Intermittent team member Ken Levine now looks to be on board for the long haul, filling the designer slot soon to be vacated by Jeff [Yaus]. Jeff in turn is heading off to work on the Golf line. 1997-04-04 Looking Glass Project Diary

I ended up working half-time on Thief and half-time on a Star Trek: Voyager game which Looking Glass had been hired to do, which never shipped. Rob [Fermier] and Jon [Chey] were on that project, and that’s where I met them. We hit it off. –Ken Levine (2016)

I ended up working half-time on Thief and half-time on a Star Trek: Voyager game which Looking Glass had been hired to do, which never shipped. Rob [Fermier] and Jon [Chey] were on that project, and that’s where I met them. We hit it off. –Ken Levine (2016)

It behooves me to note that reports of Jeff’s demise were exaggerated. Would-be replacement Ken Levine is going to be leaving LG for greener pastures. –1997-04-28 Looking Glass Project Diary

Ken Levine, Rob Fermier and I were developers at Looking Glass, struggling with the aftermath of Voyager, an aborted Star Trek: Voyager-licensed project. At the time, Looking Glass was in financial and creative disarray after a series of titles that, though critically acclaimed, had failed to meet sales expectations, the latest being Terra Nova and British Open Championship Golf. Frustration with the 18 months wasted on Voyager and a certain amount of hubris prompted three of us to strike out on our own to test our game design and management ideas. –Jonathan Chey (1999)

Ken Levine, Rob Fermier and I were developers at Looking Glass, struggling with the aftermath of Voyager, an aborted Star Trek: Voyager-licensed project. At the time, Looking Glass was in financial and creative disarray after a series of titles that, though critically acclaimed, had failed to meet sales expectations, the latest being Terra Nova and British Open Championship Golf. Frustration with the 18 months wasted on Voyager and a certain amount of hubris prompted three of us to strike out on our own to test our game design and management ideas. –Jonathan Chey (1999)

Vijay Lakshman was in charge of the project [when it was Dark Camelot] and he was the producer. […] He’s not even mentioned in the credits. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Vijay Lakshman was in charge of the project [when it was Dark Camelot] and he was the producer. […] He’s not even mentioned in the credits. -Brennan Priest (2016)

I do know there was a serious, major rewrite after Thief had been in production for about a year. They decided that “This just isn’t going to work, the way it’s progressing right now”. They pretty much stopped production and threw out a lot of the design and coding work that had been done up to that point and basically started over. […] So maybe that had something to do with it. -Steve Pearsall (2017)

I do know there was a serious, major rewrite after Thief had been in production for about a year. They decided that “This just isn’t going to work, the way it’s progressing right now”. They pretty much stopped production and threw out a lot of the design and coding work that had been done up to that point and basically started over. […] So maybe that had something to do with it. -Steve Pearsall (2017)

We went through a bunch of different phases of reorganizing the project structure and a bunch of us got sucked on to doing some other project work on Flight [Unlimited] and stuff, and there was all this chaos. We said, “OK, well, we’ve got to get this going and really focus and make a plan.” So we put Greg [LoPiccolo] in charge of the project and we agreed we were going to call it Thief and we were going to focus much more. That’s when we went from lots of playing around and exploring to “Let’s make this thief game.” -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

We went through a bunch of different phases of reorganizing the project structure and a bunch of us got sucked on to doing some other project work on Flight [Unlimited] and stuff, and there was all this chaos. We said, “OK, well, we’ve got to get this going and really focus and make a plan.” So we put Greg [LoPiccolo] in charge of the project and we agreed we were going to call it Thief and we were going to focus much more. That’s when we went from lots of playing around and exploring to “Let’s make this thief game.” -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

I was actually project director for Thief for a few months before I got lured away by a couple of my former MIT classmates to work at Harmonix which at that point was another tiny startup with around seven people. I handed Thief onto the head of our audio vision department whose name was Greg LoPiccolo. –Dan Schmidt (2011)

When I came on, the game was still in the midst of finding its vision, so we missed a lot of deadlines – largely because all these design ideas were new, and were technically difficult to accomplish, so were hard to schedule accurately. I spent a fair amount of time just building a waterfall development schedule, so we had some sense of the overall scope. I don’t think the project had a detailed development schedule until I made one – which was helpful in getting us organized to complete the project. -Greg LoPiccolo (2018)

When I came on, the game was still in the midst of finding its vision, so we missed a lot of deadlines – largely because all these design ideas were new, and were technically difficult to accomplish, so were hard to schedule accurately. I spent a fair amount of time just building a waterfall development schedule, so we had some sense of the overall scope. I don’t think the project had a detailed development schedule until I made one – which was helpful in getting us organized to complete the project. -Greg LoPiccolo (2018)

Full development began in May 1997 with a team comprised almost entirely of a different group of people from those who started the project. –Tom Leonard (1999)

Full development began in May 1997 with a team comprised almost entirely of a different group of people from those who started the project. –Tom Leonard (1999)

Of course, the big news this week is LG’s merger with the games division of Intermetrics. Obviously, there’s a lot more to be said about such a thing than I can say here, and really the only relevant thing is that through the whole deal everyone was really psyched about both The Dark Project and Flight Unlimited II, which is gratifying. –Tim Stellmach (1997)

Of course, the big news this week is LG’s merger with the games division of Intermetrics. Obviously, there’s a lot more to be said about such a thing than I can say here, and really the only relevant thing is that through the whole deal everyone was really psyched about both The Dark Project and Flight Unlimited II, which is gratifying. –Tim Stellmach (1997)

Looking Glass’s salvation was Intermetrics, who acquired the studio and gave it a couple more years. However, another failed project would have meant the studio’s doom. -Randy Smith (2016)

Looking Glass’s salvation was Intermetrics, who acquired the studio and gave it a couple more years. However, another failed project would have meant the studio’s doom. -Randy Smith (2016)

I believe that Eidos was already on board as a publisher when I came onto the project. It was part of my job to interface with them to keep them up to date on our development progress. -Greg LoPiccolo (2018)

I believe that Eidos was already on board as a publisher when I came onto the project. It was part of my job to interface with them to keep them up to date on our development progress. -Greg LoPiccolo (2018)

I have the original booklet that I created with all the concept art to send to Eidos, Microsoft, etc. -Brennan Priest (2016)

I have the original booklet that I created with all the concept art to send to Eidos, Microsoft, etc. -Brennan Priest (2016)

Voyager was the first professional project of mine to fall entirely apart, and it left me with something to prove myself on Thief. -Tim Stellmach (2016)

Although a multiplayer mode is currently planned, it will only include the usual deathmatch scenarios. A special multiplayer version of Dark is currently being considered. –PC Games (1997-03)

The design team is putting the finishing touches on the final production version of the design specifications (especially our novel multiplayer “Theftmatch” mode, which owes a lot to the efforts of Dorian [Hart] and Doug). –1997-07-11 Looking Glass Project Diary

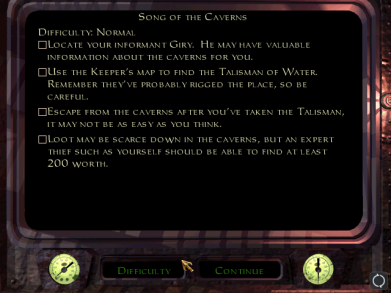

Early on, the Thief plan was chock full of features and metagame elements: lots of player tools and a modal inventory user interface to manage them; multiplayer cooperative, death-match and “Theft-match” modes; a form of player extra-sensory perception; player capacity to combine world objects to create new tools; and branching mission structures. These and other “cool ideas” were correctly discarded. –Tom Leonard (1999)

Early on, the Thief plan was chock full of features and metagame elements: lots of player tools and a modal inventory user interface to manage them; multiplayer cooperative, death-match and “Theft-match” modes; a form of player extra-sensory perception; player capacity to combine world objects to create new tools; and branching mission structures. These and other “cool ideas” were correctly discarded. –Tom Leonard (1999)

I sent a whole design document [to the team] about the multiplayer design of Thief, which had been mentioned in the original design document but very thinly and I had a lot of very strong multiplayer […] ideas. That was one that did not get received very well because the programmers and producers understood the role of multiplayer in a production: How likely it is to get cut, how expensive it is, how difficult it is to debug and design and produce. –Randy Smith (2011)

I sent a whole design document [to the team] about the multiplayer design of Thief, which had been mentioned in the original design document but very thinly and I had a lot of very strong multiplayer […] ideas. That was one that did not get received very well because the programmers and producers understood the role of multiplayer in a production: How likely it is to get cut, how expensive it is, how difficult it is to debug and design and produce. –Randy Smith (2011)

In later versions, it may well be possible to have several people playing along. The engine is in principle suitable for multiplayer rounds, and we think about a cooperation mode. Another option is team play, where you may have to find a treasure. However, the concept is initially designed for solo players, where it unfolds its greatest strengths. –Greg LoPiccolo (1998-07 PC Player)

In later versions, it may well be possible to have several people playing along. The engine is in principle suitable for multiplayer rounds, and we think about a cooperation mode. Another option is team play, where you may have to find a treasure. However, the concept is initially designed for solo players, where it unfolds its greatest strengths. –Greg LoPiccolo (1998-07 PC Player)

It’s important to stress the role of planning because in a creative business it’s all too easy to get swept up in your ideas and just improvise as you go along. Generally this leads to work that’s sloppier and less focused than what you’re really capable of. Think about what you’re trying to do overall before you even start work on any individual part. Don’t go off half-cocked. -Tim Stellmach (2000)

It’s important to stress the role of planning because in a creative business it’s all too easy to get swept up in your ideas and just improvise as you go along. Generally this leads to work that’s sloppier and less focused than what you’re really capable of. Think about what you’re trying to do overall before you even start work on any individual part. Don’t go off half-cocked. -Tim Stellmach (2000)

We wanted to push the envelope in almost every element of the code and design. The experimental nature of the game design, and the time it took us to fully understand the core nature of that design, placed special demands on the development process. The team was larger than any Looking Glass team up until then, and at times there seemed to be too many cooks in the kitchen. Reaching a point where everyone shared the same vision took longer than expected. –Tom Leonard (1999)

We wanted to push the envelope in almost every element of the code and design. The experimental nature of the game design, and the time it took us to fully understand the core nature of that design, placed special demands on the development process. The team was larger than any Looking Glass team up until then, and at times there seemed to be too many cooks in the kitchen. Reaching a point where everyone shared the same vision took longer than expected. –Tom Leonard (1999)

It’s hard to design missions around gameplay experiences you haven’t really seen before. In production, it wasn’t even really clear to us which parts of playing the thief character people would respond to. -Tim Stellmach (2000)

It’s hard to design missions around gameplay experiences you haven’t really seen before. In production, it wasn’t even really clear to us which parts of playing the thief character people would respond to. -Tim Stellmach (2000)

For Thief we had a huge advantage because at the end of the day we could say, “Well, is it making the character more thief-y? Hmm, that looks like it makes him stronger and brawnier, probably don’t need that. Hmm, that looks like it makes him cooler and stealthier, let’s do that.” Not all games that try to innovate have such an easy focus, but I think that was a crucial part of Thief. You could always go “Is the thing I’m typing going to make him stealthier?” -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

For Thief we had a huge advantage because at the end of the day we could say, “Well, is it making the character more thief-y? Hmm, that looks like it makes him stronger and brawnier, probably don’t need that. Hmm, that looks like it makes him cooler and stealthier, let’s do that.” Not all games that try to innovate have such an easy focus, but I think that was a crucial part of Thief. You could always go “Is the thing I’m typing going to make him stealthier?” -Doug Church (Rouse 2005)

Just calling it Thief and making it about being a thief, it created the context. –Paul Neurath (2018)

Just calling it Thief and making it about being a thief, it created the context. –Paul Neurath (2018)

In Thief 1 we hadn’t identified that yet at the start as to like ‘This is a stealth game’. We start with ‘This is a thief game’ and we were looking at quite a lot of points of reference of what a thief could be. Dungeons & Dragons was one of them, the Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories, and the Batman comics. Batman in the role of Garrett. He’s not a thief but a lot of the stealth moment there actually came from that.

In Thief 1 we hadn’t identified that yet at the start as to like ‘This is a stealth game’. We start with ‘This is a thief game’ and we were looking at quite a lot of points of reference of what a thief could be. Dungeons & Dragons was one of them, the Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories, and the Batman comics. Batman in the role of Garrett. He’s not a thief but a lot of the stealth moment there actually came from that.

I remember at the time really thinking a lot about – I don’t know if anyone now remembers – the game Thieves Guild by this small press outlet called Gamelords. […] In their printed supplements, in Thieves Guild, they organized things by these categories of thieving activity that you would do. They had a chapter which was like “Pickpocket Scenarios” and “Armed Robbery Scenarios” and “Burglary Scenarios” and “Tomb Robbing”. I went back to that at that time and based on – not just that list – we started brainstorming “What are all the thievy things that you could do?” –Tim Stellmach (2011)

The key was we wanted to make sure you had active tools to be stealthy. You weren’t just hiding all the time. […]

The key was we wanted to make sure you had active tools to be stealthy. You weren’t just hiding all the time. […]

I was involved in the initial ideas like coming up with that you would use your bow to project things like moss to make things on the ground, to knock out lights, and noise-maker arrows. In terms of making that work and actually making that feel good, a lot of other people took that over. –Ken Levine (2011)

We’re giving a few interested parties tryouts on level editing to help fill the gap left by Jeff’s recent departure from the team (looks like for good this time). No, that’s not a job opening as such … but you may be seeing some further changes in the team coming up. –1997-07-18 Looking Glass Project Diary

I was sort of a backfield designer. I was only half-time so I wasn’t in charge of any levels. A lot of the stuff that I did was script dialogue. “Okay, come up with ten different ways for a guard to say ‘I think maybe I’ve heard something.’ Then ten more ways for when they’ve maybe seen something, then ten more for when they’ve definitely seen something.“ That was a lot of writing into spreadsheets. I did conversations, I did editing motion captures. –Laura Baldwin (2011)

I was sort of a backfield designer. I was only half-time so I wasn’t in charge of any levels. A lot of the stuff that I did was script dialogue. “Okay, come up with ten different ways for a guard to say ‘I think maybe I’ve heard something.’ Then ten more ways for when they’ve maybe seen something, then ten more for when they’ve definitely seen something.“ That was a lot of writing into spreadsheets. I did conversations, I did editing motion captures. –Laura Baldwin (2011)

On the design side, we’ve brought on a new designer part-time in the person of one Laura Baldwin. She’s getting started on mission design. –1997-10-03 Looking Glass Project Diary

The Looking Glass website had a teaser for The Dark Project, promising a rich world of stealth gameplay. I had a computer science degree with minors in psychology and media arts, but no experience. Looking Glass wasn’t listing any openings, so I tracked down the project director, Greg LoPiccolo. -Randy Smith (2016)

The Looking Glass website had a teaser for The Dark Project, promising a rich world of stealth gameplay. I had a computer science degree with minors in psychology and media arts, but no experience. Looking Glass wasn’t listing any openings, so I tracked down the project director, Greg LoPiccolo. -Randy Smith (2016)

They sent me back with homework, with their level editor. They wanted me to build a level and show that I had some design instincts. –Randy Smith (2011)

Things are really gearing up around here. I’d like to welcome a new member of our design team, Randy Smith. Like Laura, Randy’s new to the games industry, but he brings much-appreciated programming skills and a background in AI to the team. –1997-10-31 Looking Glass Project Diary

Really early on in my career they were like, “You know, you’re not such a great programmer, but you’re pretty good at design. So why don’t you stop with that whole programming thing and you can be a level builder for us?” –Randy Smith (2011)

Really early on in my career they were like, “You know, you’re not such a great programmer, but you’re pretty good at design. So why don’t you stop with that whole programming thing and you can be a level builder for us?” –Randy Smith (2011)